PASTOR Wilson Isnord, a tall, youthful leader in the Haitian community, walked through puddles of water and piles of trash with a blowhorn in hand as rain fell from overcast skies, shouting a simple message in Creole and English: “Get out and evacuate.”

Defence Force officers accompanied him through the Mudd and Pigeon Peas of Abaco some 12 hours before Hurricane Dorian made landfall last Sunday.

There were dilapidated houses densely packed together, throngs of electrical wires illegally strewn from house to house, and piles of garbage seemingly not collected for weeks – all the trappings of life in these sprawling shantytowns -the country’s two largest, before Dorian decimated them.

Music blared from speakers. Men crowded into barber shops to get haircuts. Cats, dogs and chickens roamed the area. Children played in the mud.

Some people gathered and listened to Pastor Isnord’s pleas, others mocked him, but most paid him no mind.

Several people, including a man with an 11-month-old child in his arms, said they didn’t know where the shelters were and therefore didn’t plan to go.

The scene remained lively with activity – but not evacuation – when The Tribune passed the area six hours before the storm hit.

Less than 10 hours later, the Mudd and Pigeon Peas would be gone and hundreds would be feared dead under its rubble.

Regardless of socio-economic backgrounds, during the storm, experiences of all Abaconians seemed to converge when Hurricane Dorian struck. Many, not familiar with severe flooding in areas like Murphy Town and Dundas Town, were stunned to suddenly be trapped in closets or on roofs, and they used the lull that came with the passage of the eye to seek shelter and higher ground.

But for many in the shantytowns the density of the buildings and the roughness of the landscape made escape impossible.

Residents there thought they had enough time to observe how strong the storm would be and determine whether evacuation was necessary.

“We didn’t leave because we were being hard-headed,” said Peria, a 23-year-old, newly married, one-month pregnant woman who escaped the Pigeon Peas in the arms of her 26-year-old husband Cliff alongside her two young children.

The Tribune met the young couple at the government complex on Wednesday morning as they headed outside seeking somewhere to bathe.

“Most people don’t evacuate during storms,” Cliff said. “They wait to see the storm for themselves and that’s when they decide. Also, the times we were hearing were inaccurate. First they said it was supposed to come this time and this time, and later and later, so we kept moving up and down, back and forth until people stopped leaving.”

For law enforcement and government officials watching the storm through the windows of the government complex, the scene during the lull was staggering.

They watched as seemingly thousands of people from the Mudd and Pigeon Peas seeped through the tall, intricate bushes that separate the complex from the shantytowns and from the roadways that surround the area.

Abaco island administrator Maxine Duncombe made a command decision to open up the complex, home to government departments from the National Insurance Board to the Bahamas Agricultural & Industrial Corporation, to the now displaced residents fleeing the storm. In the subsequent days, people slept in hallways, on desks, tables, chairs, or while standing up. Many couldn’t sleep at all and the complex buzzed with human activity throughout the nights.

Reporters were warned not to walk barefoot in the corridors because people had been urinating and defecating on ground.

“We saw people get carry before our eyes,” Cliff said about escaping the Peas during the storm. “We had two children and had to swim out of 30 feet of surging water. It even carried my wife. I had to hold on to her. I had no idea what would happen. We knew it would flood, but we thought it would gradually grow; but I watched the water grow from a foot to 30 feet in about three minutes.”

Turning to his wife, Cliff eyes’ bulged. “I seen Cybil’s mother who’s dead,” he said, “her head is swollen already, her head and face. I seen it kill two people at one time between two buildings. Things were flying and knocking down people trying to run. One is my friend and one is his mother. His mother was with us but he had to get his son out, he got his son out but he died when he went back for his mother.”

Cliff’s story was almost identical to that told by Kevin Altidor, a professional basketball player in Europe whose nephew, Brenden Dion Altidor, spent the hurricane on a tree where he had been placed by his stepfather who went back to rescue his mother.

Like many, Cliff’s wife Peria said her family lost all their identification documents, prompting concern about what her fate will ultimately be in the Bahamas. She said she was a Bahamian citizen.

She matter of factly revealed that her mother was killed during the storm.

“I feel like when it will hit me is when I have to disclose that to my 13-year-old sister, my 15-year-old brother living in the States, and my mother also has a 26-year-old living in Jamaica studying to be a brain surgeon, so he doesn’t know that she’s dead.”

“I saw my house in the Peas and my house is resting on top of a dead body, and that dead body been there since Sunday and it’s now Wednesday,” she said. Though pregnant, she had not seen a doctor up to the time she spoke to The Tribune, fearing that they would transport her to Nassau and separate her from her family.

When Dorian’s winds weakened, displaced residents at the shelter – just like residents elsewhere on the island – began to loot. They pushed trolleys back and forth from the Save-A-Lot warehouse to the government complex, sometimes making multiple trips. They carried water, packaged foods and alcohol. Some stripped naked and bathed in broad daylight.

They washed clothes they somehow salvaged and hung them out to dry on the trees surrounding the government complex.

Some visited the Mudd and Peas after the storm, hoping to salvage valuables, but mostly recovering nothing from the rubble. Some beckoned to people passing them by, saying: “Come see the dead body.” This included bodies of three people who were crushed under the roof of a church just outside the Peas; eight people had evacuated there during the storm, the condition of five of them unknown.

On Wednesday, The Tribune found Mr Isnord, the Haitian pastor, at the government complex.

Although he lived in Central Pines, he too had escaped to the complex with his family after the windows in his house blew out and the water began to rise.

“Everyone here has a story to tell about persons who died,” he said. “The mental state is terrible. People are traumatised, trying to cope with the situation the best way they can. You don’t know what is next, don’t know what the plans are, so whatever we can do to make things better, we are doing it.”

Some of the residents, unable to speak English, walked up to reporters that had recording devices, begging in Creole that their messages be recorded and taken to family and friends outside Abaco.

Some talked openly about wanting to rebuild the Mudd.

“These people won’t let us stay here, ma boy, that’s why I took four bags of cement and will rebuild as soon as the floods go down,” one man said.

Many others just want to leave Abaco behind.

More from LOCAL

Sands cannot live without washed-up Ingraham. It’s so sad.

The Bahamas is once again being asked to suspend disbelief. We are being told that Duane Sands stands as an …

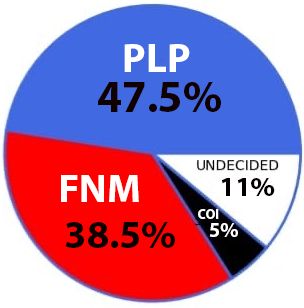

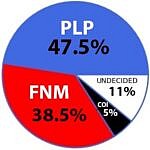

Recent Poll Shows Strong Confidence in PLP Leadership and Doubts About FNM Stability

A recent unscientific poll, conducted among Bahamians ages 18 to 60 in the "over the hill" area, shows the Progressive …

ZANE LIGHTBOURNE, MORE ACTION, LESS TALK.

In politics today, noise often masquerades as leadership. Grand speeches trend online. Manufactured outrage fills timelines. But in Yamacraw, residents …